A DREAM DEFERRED

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore--

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over--

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

The above piece was written by the poet Langston Hughes. It is a powerful statement that addresses not only the condition of being poor, or being a minority, but about being a human who dreams and the supreme disappointment one feels when that dream is not allowed to be realized, or even worse, is crushed and destroyed.

I relate. God, how I relate!

A poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist, I discovered Langston in my 7th grade English class. Our teacher, Miss Sally Harper stood before us and read one of his poems to the class. Strangely, no one seemed very interested or intrigued by those words being read to us. No one really seemed to GET IT, but me. "Weirdo!"

I was soon inspired to write a similar poem. Trust. It paled in comparison, because I was 12 or 13, trying to write like Langston, and not like myself. I had so much to learn.

Suddenly, I wanted to inhale that same Harlem air, and to bathe inside his poetic brilliance. Suddenly, I wanted to do what he did, and to walk in his footsteps. And mind you, he'd set the bar mighty high!

This was my introduction to him, to his gift, his awesome wordsmithery, his unique rhythm, his sensibility and his mastery of the written/spoken word.

In fact, I can truthfully state that it was the work, the voice and the vision of Langston Hughes which inspired me to become a poet. Before I graduated high school, my first poem was published in a national magazine (Young America Sings). Langston gets at least partial credit for this accomplishment because, before him, I never knew that moving people with the sheer power of words was even possible.

* * *

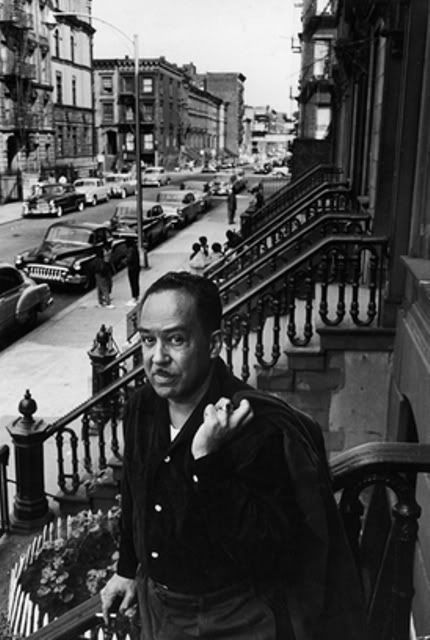

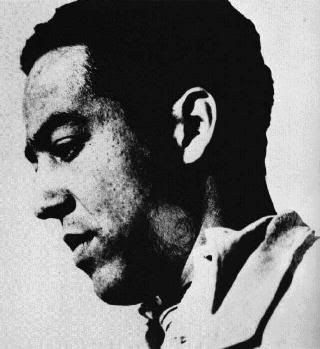

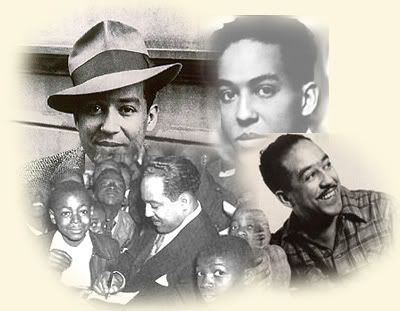

(James) Langston Hughes began writing in high school, and even at this early age was developing the voice that made him famous. Hughes was born on February 1, 1902. He was a native of Joplin, Missouri, but lived with his grandmother in Lawrence, Kansas until he was thirteen and then with his mother in Lincoln, Illinois and Cleveland, Ohio where he went to high school. Hughes's grandmother, Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston, was prominent in the African American community in Lawrence. Her first husband had died at Harper's Ferry fighting with John Brown; her second husband, Langston Hughes's grandfather, was a prominent Kansas politician during Reconstruction.

During the time Hughes lived with his grandmother, however, she was old and poor and unable to give Hughes the attention he needed. Besides, Hughes felt hurt by both his mother and his father, and was unable to understand why he was not allowed to live with either of them. These feelings of rejection caused him to grow up very insecure and unsure of himself.

When Langston Hughes's grandmother died, his mother summoned him to her home in Lincoln, Illinois. Here, according to Hughes, he wrote his first verse and was named class poet of his eighth grade class. Hughes lived in Lincoln for only a year, however; when his step-father found work in Cleveland, Ohio, the rest of the family then followed him there. Soon his step-father and mother moved on, this time to Chicago, but Hughes stayed in Cleveland in order to finish high school. His writing talent was recognized by his high school teachers and classmates, and Hughes had his first pieces of verse published in the Central High Monthly, a sophisticated school magazine. Soon he was on the staff of the Monthly, and publishing in the magazine regularly.

An English teacher introduced him to poets such as Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman, and these became Hughes' earliest influences. During the summer after Hughes's junior year in high school, his father reentered his life. James Hughes was living in Toluca, Mexico, and wanted his son to join him there. Hughes lived in Mexico for the summer but he did not get along with his father. This conflict, though painful, apparently contributed to Hughes's maturity. When Hughes returned to Cleveland to finish high school, his writing had also matured. Consequently, during his senior year of high school, Langston Hughes began writing poetry of distinction.

* * *

Mother to Son

________________________________________

Well, son, I'll tell you:

Life for me ain't been no crystal stair.

It's had tacks in it,

And splinters,

And boards torn up,

And places with no carpet on the floor --

Bare.

But all the time

I'se been a-climbin' on,

And reachin' landin's,

And turnin' corners,

And sometimes goin' in the dark

Where there ain't been no light.

So boy, don't you turn back.

Don't you set down on the steps

'Cause you finds it's kinder hard.

Don't you fall now --

For I'se still goin', honey,

I'se still climbin',

And life for me ain't been no crystal stair.

Hughes entered Columbia University in the fall of 1921, a little more than a year after he had graduated from Central High School. Langston stayed in school there for only a year; meanwhile, he found Harlem. Hughes quickly became an integral part of the arts scene in Harlem, so much so that in many ways he defined the spirit of the age, from a literary point of view. The Big Sea, the first volume of his autobiography, provides such a crucial first-person account of the era and its key players that much of what we know about the Harlem Renaissance we know from Langston Hughes's point of view. Hughes began regularly publishing his work in the Crisis and Opportunity magazines. He got to know other writers of the time such as Countee Cullen, Claude McCay, W.E.B. DuBois, and James Weldon Johnson. When his poem "The Weary Blues" won first prize in the poetry section of the 1925 Opportunity magazine literary contest, Hughes's literary career was launched. His first volume of poetry, also titled The Weary Blues, appeared in 1926.

Epilogue

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll sit at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

"Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed.

I, too, am America.

From The Weary Blues by Langston Hughes,

Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1926.

Du Bose Heyward wrote in the New York Herald Tribune:

"Langston Hughes, although only twenty-four years old, is already conspicuous in the group of Negro intellectuals who are dignifying Harlem with a genuine art life. . . It is, however, as an individual poet, not as a member of a new and interesting literary group, or as a spokesman for a race that Langston Hughes must stand or fall. . . Always intensely subjective, passionate, keenly sensitive to beauty and possessed of an unfaltering musical sense, Langston Hughes has given us a 'first book' that marks the opening of a career well worth watching."

In Langston Hughes's poetry, he uses the rhythms of African American music, particularly blues and jazz. This sets his poetry apart from that of other writers, and it allowed him to experiment with a very rhythmic free verse. Hughes's second volume of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927), was not well received at the time of its publication because it was too experimental. Now, however, many critics believe the volume to be among Hughes's finest work.

The Negro Speaks Of Rivers

(To W.E.B. DuBois)

I've known rivers:

I've known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I've seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I've known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

Langston Hughes was, in his later years, deemed the "Poet Laureate of the Negro Race." It was a title he encouraged.

Hughes meant to represent the race in his writing and he was, perhaps, the most original of all African American poets. On May 22, 1967 Langston Hughes died after having had abdominal surgery. Hughes' funeral, like his poetry, was all blues and jazz: the jazz pianist Randy Weston was called and asked to play for Hughes's funeral. Very little was said by way of eulogy, but the jazz and the blues were hot, and the final tribute to this writer so influenced by African American musical forms was fitting.

* * *

In Praise Of Langston

By. L.M. Ross

I’ve sang your songs

My whole life long. Inside my head

Your songs play daily, nightly. They

Rumble rhythmically in the subways and

Holler mightily from the pews of Baptist churches.

Your songs serenade old & new lovers. They soar high

Over these "Negro Streets", leave their bleat over Birdland's

Jazz like beautiful black & orange robins... And even they

Will s-i-g-h... cry out.... and caw... your name: Langston!”

Oh Langston!

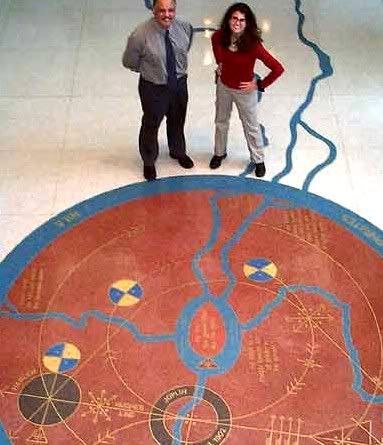

To honor you, in Harlem

They’ve placed your ashes

Beneath the Schomburg Museum’s floor.

You rest there, our most eloquent father,

Our most poetic warrior, watching over us, as

You always did… part sentinel, part solider...

Oh Langston! Are you charting our heartbeats? Oh, Langston!

Are you ghost-walking

These streets, still

Marveling at our beauty? Are you

Looking to crash the nearest "rent party"...

Nodding your head to our hip-hop? Or perhaps

You are even smiling... Yes... Smiling... just

A little bit... At the rhythm, the rhythm of our

Swagger. . . and the footsteps, the footsteps

Of our Progress.

One.

© 2012 by L.M.Ross moaningmanblues All Rights Reserved