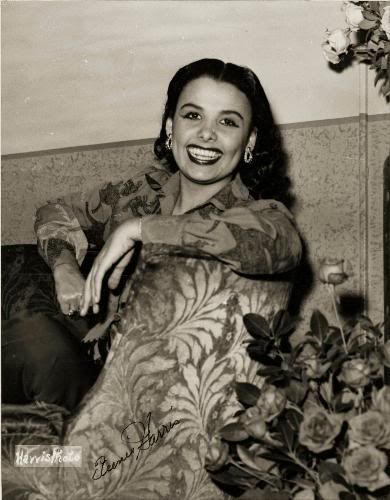

Yesterday, on Mother’s Day, the world lost a genuine legend. Lena Horne, who possessed a uniquely silk and bourbon voice, accented by her rich copper-skinned goddess-like beauty has passed. Perhaps, best known for her rendition of the 1940s torch song “Stormy Weather,” Miss Lena, 92, died in her native, NYC, at New York Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center.

She was born Lena Mary Calhoun Horne on June 30, 1917, in Brooklyn, N.Y.

She began performing at the tender age of sixteen, as a chorus girl at the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem. This was way back in 1933, and Miss Lena's career would continue for an astounding six-decades, which included films, radio, television, recording, nightclubs, concert halls and Broadway.

Her talent and other-worldly beauty were undeniable. At her core, she was a singer, and she never wanted to become an actress, but then Hollywood came knocking. At the insistence of her friend, Count Basie, this was to be her destiny. He told her that she was blessed to have been The Chosen One, and so she had to represent black people in ways other than pickaninnies and maids. A reluctant Lena agreed. She went to Hollywood, signed with MGM Studios, and made a handful of movies, many of which edited out her performances, before being shown in the Jim Crow south.

She made a few classic Hollywood musicals, including Cabin in the Sky, and Stormy Weather, both released in 1943.

With her fair skin, strong bone structure and dazzling smile, she was a breakthrough on the silver screen — "Hollywood’s first black beauty, sex symbol, singing star," as Vogue magazine put it decades later.

"I was unique in that I was a kind of black that white people could accept," Horne once said. "I was their daydream. I had the worst kind of acceptance because it was never for how great I was or what I contributed. It was because of the way I looked."

A World War II pinup girl, the glamorous Miss Lena in 1944 became the first black to appear on the cover of a movie magazine, Motion Picture.

"Anybody who was not madly in love with Lena Horne should report to his undertaker immediately and turn himself in," actor and friend Ossie Davis said on "Lena Horne: In Her Own Voice," a 1996 installment of PBS’ "American Masters" biography series.

"In the history of American popular entertainment, no woman had ever looked like Lena Horne. Nor had any other black woman had looks considered as ’safe’ and non-threatening," Donald Bogle wrote in his book "Brown Sugar: Over One Hundred Years of America’s Black Superstars."

Although, at the time, she was considered the highest paid black woman in America, Hollywood never did right by Miss Lena. They wanted her, and yet didn’t know what to do with her. Lena refused to pass as anything other than what she was, and glamourous black woman of a particular light complexion could only go so far on film.

The one role she’d actually coveted, that of Julie, the tragic mulatto in the musical Showboat went instead to her beauteous white friend, Ava Gardner. Miss Gardner herself protested this casting and would had perferred Lena to play and sing the part, but the suits felt differently. Miss Gardner appeared, and had her singing dubbed. This was a tremedous slap in Lena’s face, and would forever leave a bad taste in her mouth.

Luckily, she still had her voice, and what a wondrous and glorious voice it was! With its smooth, carressing tonality and slightly seductive drawl, she would fit well into that pantheon of great female jazz singers including, Ethel Waters, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Carmen McRae."

Miss Lena modestly disagreed:

"Oh, please," she said. "I’m really not Miss Pretentious. I’m just a survivor. Just being myself."

During her early New York roots, she made her Broadway debut in 1934 with a small role in "Dance With Your Gods," an all-black drama that ran only nine performances.

Later, she became a featured singer in the all-black Noble Sissle Society Orchestra but quit two years later to marry Louis Jones, a Pittsburgh friend of her father’s who was some nine years her senior.

At 19, she settled into domestic life in Pittsburgh and gave birth to her two children, Gail and Teddy. But she and her husband separated in 1940 and were divorced in 1944.

She gave up show business when she married Jones, however money problems during the marriage prompted her to accept the co-starring role in "The Duke Is Tops," a low-budget, 1938 black movie musical shot in 10 days.

Moving back to New York after her marriage dissolved, she was hired as a vocalist with the Barnet Orchestra, becoming one of the first black performers to sing with a major white band, with whom she had a hit record, "Good for Nothing Joe."

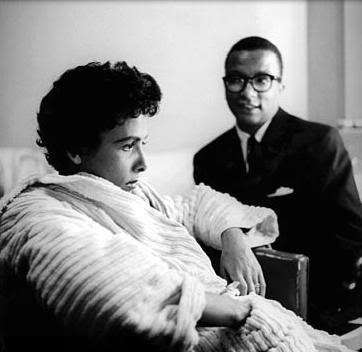

After leaving the Barnet band in 1941, Miss Lena began an extended engagement at Cafe Society Downtown, where she first met and became friends with singer-actor and political activist Paul Robeson.

While under contract to MGM in the ’40s, Horne met Lennie Hayton, a white staff composer and arranger at the studio who became her second husband. Fearing public reaction, they did not announce their marriage until three years later. She admitted later that she’d initially became involved with Hayton because she thought he could be useful to her career.

"He could get me into places no black manager could," she told The New York Times [NYT] in 1981. "It was wrong of me, but as a black woman, I knew what I had against me." But, she said, "because he was a nice man and because he was in my corner, I began to love him."

Miss Lena had publicly stated that her One True Love and Soulmate was Lush Life composer and one-time Ellington songwriting partner, Billy Strayhorn. They loved each other deeply. They were such great friends; they even completed each other's sentences. She’d stated how she desperately wanted to marry him. The only roadblock to her bliss was that Strayhorn was an openly gay man. She was devastated by his early death.

Sadly, it appeared that throughout her long life and enduring career, true love and a happy marriage would forever escape her grasp.

Primarily due to her friendship with the bold and outspoken Paul Robeson coupled with her involvement with the Council for African Affairs and the Hollywood Independent Citizens Committee to the Arts, Science and Professions, both of which were named as Communist fronts, Horne found herself blacklisted and unable to appear on radio and television in the early ’50s. But the cabaret business remained untouched by the blacklist, and she focused on her critically acclaimed nightclub/cabaret act.

Her Lena Horne at the Waldorf Astoria became RCA Victor’s biggest-selling album by a female vocalist in 1957.

Horne, who was able to resume appearing on television in 1956, also starred in the hit Broadway musical "Jamaica," which ran from 1957 to ’59 and earned her a Tony Award nomination.

Unable to stay in many of the hotels she performed in because she was black, Miss Lena developed what she later described as "a toughness, a way of isolating" herself from the audience as a performer.

Throughout her early career, Horne experienced the injustices suffered by African Americans at the time.

While touring with the USO during World War II, she was expected to entertain the white soldiers before the blacks. When she discovered that the whites seated in the front rows were German prisoners of war, she became furious. Marching off the platform, she turned her back on the POWs and sang to the black soldiers in the back of the hall.

Her long-suppressed anger over the treatment of blacks in white society erupted in 1960 when she overheard a drunken white man at the Luau restaurant in Beverly Hills refer to her as "just another nigger."

Jumping up, she threw an ashtray, a table lamp and several glasses at him, cutting the man’s forehead.

When reports of her outburst appeared in newspapers around the country, Horne was surprised at the positive response, mostly from African Americans.

"Phone calls and telegrams came in from all over," she told the Christian Science Monitor in 1984. "It was the first time it struck me that black people related to each other in bigger ways than I realized."

In the early ’60s, Horne became more active in the civil-rights movement, participating in a meeting with prominent blacks in 1963 with then-Attorney General Robert Kennedy in the wake of violence in Birmingham, Ala., and singing at civil rights rallies.

In the early ’70s, Horne faced three personal blows within an 18-month period: In 1970, the same year her father died, her son died of kidney disease; and her husband died of a heart attack in 1971.

Horne later said she "stayed in the house grieving" until Alan King "bullied" her out of her depression, and she returned to singing and recording.

She also toured with Tony Bennett, and performed with him in 37 performances on Broadway of "Tony & Lena Sing" in 1974.

In a brief, and noted return to the screen, she played Glinda, the Good Witch in "The Wiz," the 1978 movie musical directed by Sidney Lumet, her then-son-in-law. The film may have starred Diana Ross, but Miss Lena stole it.

“If You Believe,” an inspirational song of self-empowerment was, for me, personally, her standout vocal performace.

Then, in 1981, she made a triumphant return to Broadway in the hit "Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music." This was her epic moment. This introduced new audiences to her unique persona, and reminded older fans of just what made her so special.

Suddenly, Miss Lena had become the IT Girl again! It mattered not that she was 63 at the time. The production went on to win critical acclaim, the Drama Desk Award and a special Tony Award for her autobiographical show which ran on Broadway for more than a year and led to a Grammy Award-winning soundtrack album and a cross-country tour of the show before going to London.

As Horne said in the documentary "Lena Horne: In Her Own Voice": "My life has been about surviving. Along the way I also became an artist. It’s been an interesting journey. One in which music became first my refuge and then my salvation."

Horne was a Kennedy Center Honors recipient in 1984, and she received a lifetime achievement award from the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences in 1998.

Thank God Miss Lena was given some flowers, some honors, and long overdue recognition while she was still here and breathing air!

Note to Alicia Keys: too bad the suits couldn’t manage to get it all together and film Miss Lena’s life story before she’d passed. Still, if anyone could play her, realistically, Miss Keys gets my vote.

I was a fan, and admirer of Miss Lena Horne. She lived a long time. Her beautiful eyes saw much ugliness, and yet in the end, she’d triumphed over much of it. For this reason, I can not feel sad at her passing. Instead, I choose to celebrate the fact that she existed!

Rest in Peace, Miss Lena… you truly did make a difference!

One Love.

Lin